A table laden with collage materials and glue sticks recently greeted about a dozen students in a first-year seminar on artificial intelligence when they arrived at their class in Seabury Hall.

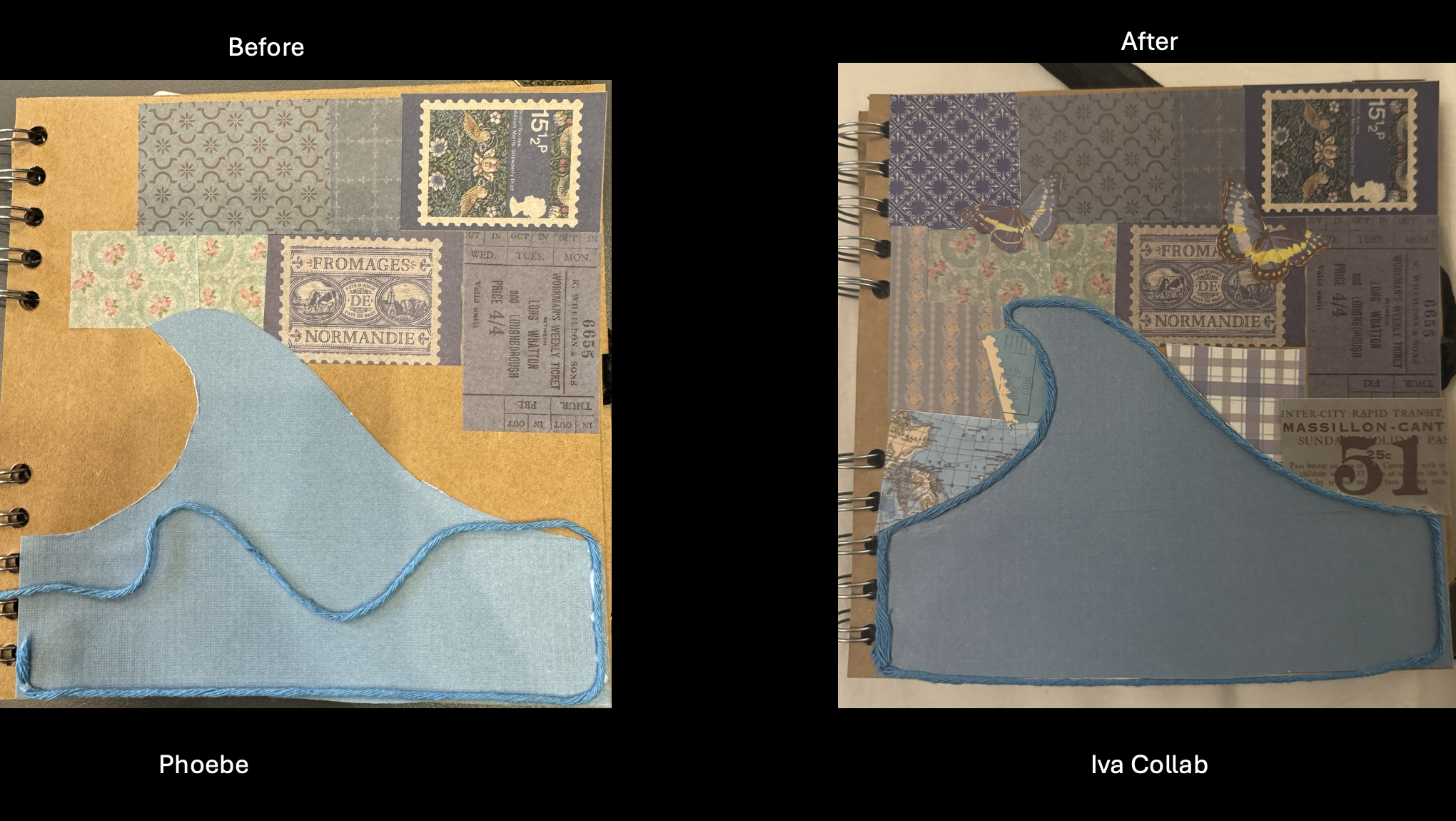

Instructions were straightforward: Ask generative artificial intelligence for an idea to pursue in a junk journal—a craft that uses of personal and recycled materials to illustrate a topic—and begin making it. Midway through the class, switch journals and pursue a classmate’s concept.

Pursuing all these endeavors is part of the curriculum about the collaborative nature of creativity and the thorny issues that sometimes raises.

“As creators, because they made it, they are approaching this not just from an intellectual point-of-view,” said Spezialetti. “They are approaching it from the heart.”

The creative projects on the syllabus for “Didn’t Humans Used to Do That? Collaborating and Co-Creating with Generative AI” are coupled with lectures about copyright law and ethics. Legal cases are cited among the examples of thorny situations involving the ownership of ideas for songs, sculptures, and more.

Collaboration has always been part of the creative process, noted Spezialetti, using a painting by Leonardo da Vinci’s mentor, Andrea del Verrocchio, as an example.

“Sometimes the need for collaboration is generated by time,” said Spezialetti, citing the example the Sagrada Família church of Barcelona.

Though its construction began in 1882, the Sagrada Família church has not yet been completed. New developments likely even altered its design. When construction on the church started a century and a half ago, the original architectural renderings presumably would not have incorporated electricity.

In other cases, collaboration is generated by physical limitations, noted Spezialetti. For example, a modern-day artist who lost vision in one of his eyes, Dale Chihuly, relies on other artists to produce the blown glass features in his pieces.

Even doing computer coding is collaborative, Spezialetti added.

Mathur fashioned the New Delhi cityscape on a page in his junk journal and later swapped with classmate Elijah Morris ’28, who was pursuing a “creepy” junk journal idea. “I always thought of visual arts as a solo thing,” said Morris.

Yet when Mathur turned his cityscape over to Morris, the artwork took a different turn. Morris made the piece it into a commentary about consumerism by adding stickers on modern pricing and satirical quotes about consumerism, “which added some real depth to the project and made it very thought-provoking,” said Mathur.

Morris said the changes reflected an artwork that was more his creation than his classmate’s.

“The final product was so different that I consider it my art piece. I’m not necessarily emotionally attached to it but I think thematically the piece was much more mine than his,” Morris said.

This semester, the students will also pursue debates and papers about the experience and ethics of co-creating with generative AI.

When it comes to being makers, “humans do not have to go it alone,” according to Spezialetti. More specifically, humans do not necessarily need to collaborate with another human. “AI can expand our capabilities,” she said.