Hamilton in Hartford: On Stage and in Trinity Classrooms

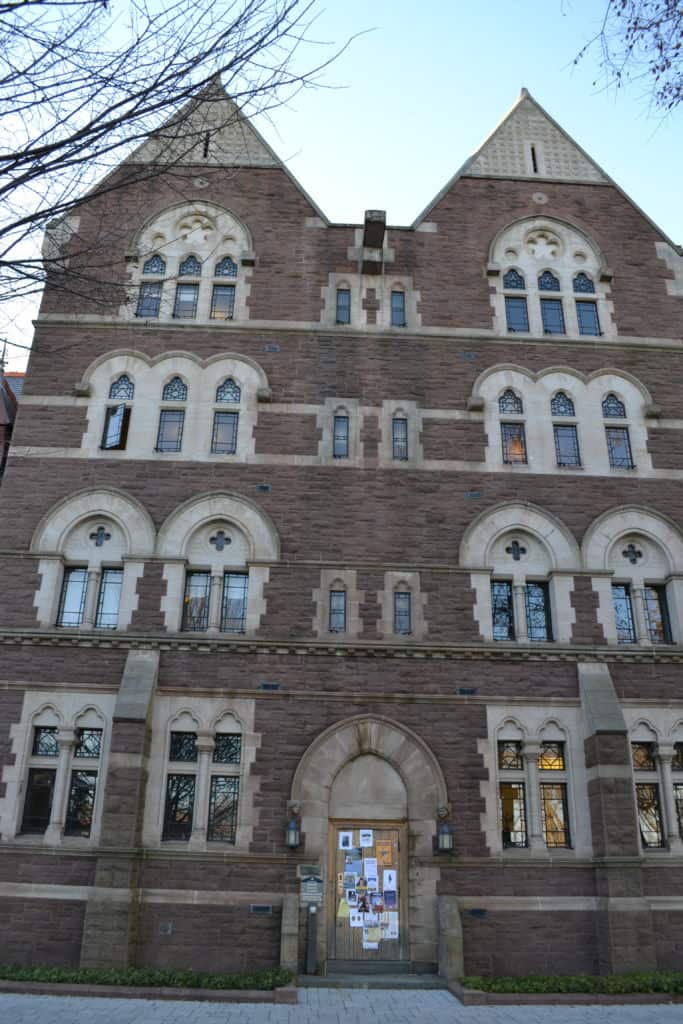

Did you know that Trinity College’s Seabury Hall is named after the same Samuel Seabury who has a musical debate about the American Revolution with the title character in the Tony Award-winning Broadway blockbuster, Hamilton?

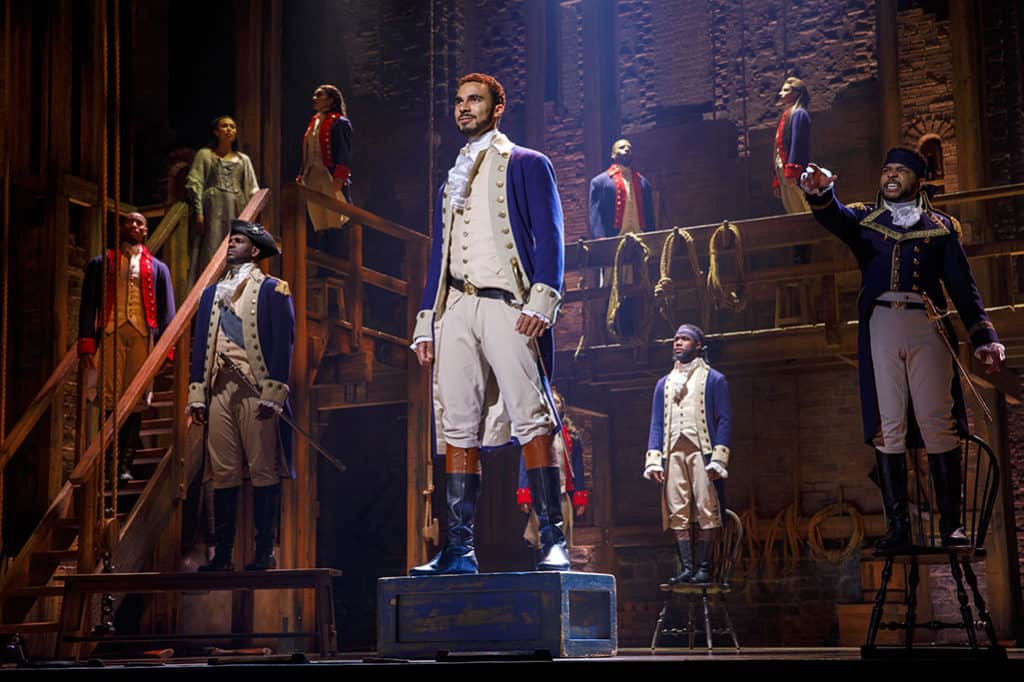

As a national tour of Hamilton opens at The Bushnell Center for the Performing Arts in Hartford on December 11, Trinity professors point out the college’s connections to the real-life historical figures portrayed on stage and share how they incorporate Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hip-hop musical about America’s founders into their academic curricula.

Assistant Professor of American Studies Alexander D. Manevitz said that he discusses Hamilton in his “Introduction to American Studies” and “Popular Narratives of U.S. History” classes at Trinity. “I talk about the musical to punctuate conversations about early American debates over federal infrastructure investment and how Americans remembered the Marquis de Lafayette, the Revolution, and the Battle of Yorktown,” he said.

Seabury, Manevitz said, was a British loyalist who wrote open letters defending King George III, just as he is portrayed in the Act One song, “Farmer Refuted,” which finds him facing off against Alexander Hamilton’s rising revolutionary rhetoric. Already ordained by the Church of England at the time of the Revolution, Seabury was at one point imprisoned by the patriots for his views. Manevitz said that Seabury later became loyal to the new American government and was consecrated as the first American Episcopal bishop and the first bishop of the Episcopal Church of Connecticut. Episcopal Bishop Thomas Brownell founded Washington College—now Trinity College—in 1823 and a Long Walk building on Trinity’s campus was eventually named in Seabury’s honor. Coincidentally, Seabury Hall now houses the offices of the American Studies Department.

In another connection between Trinity and the historical figures portrayed in Hamilton, Charles Sigourney—the first president of the Board of Trustees of Washington College—had a written correspondence in 1824 with Thomas Jefferson about the college and the state of higher education in the region, Manevitz said. Jefferson replied to Sigourney with news about his own recently-founded college, the University of Virginia.

In his classes, Manevitz also talks about how the musical communicates “mythic” versions of American history to audiences who are drawn to the contemporary and relatable aspect of incorporating hip-hop and R&B into an immigrant success story. “I use the musical to discuss the ways primary sources and other research—as well as questions of historical method and memory—are integrated into the performance subtly, teaching listeners lessons about these topics they might not even be consciously absorbing,” he said. “I saw the musical in New York. It was better than I thought it would be, and I thought it would be great.”

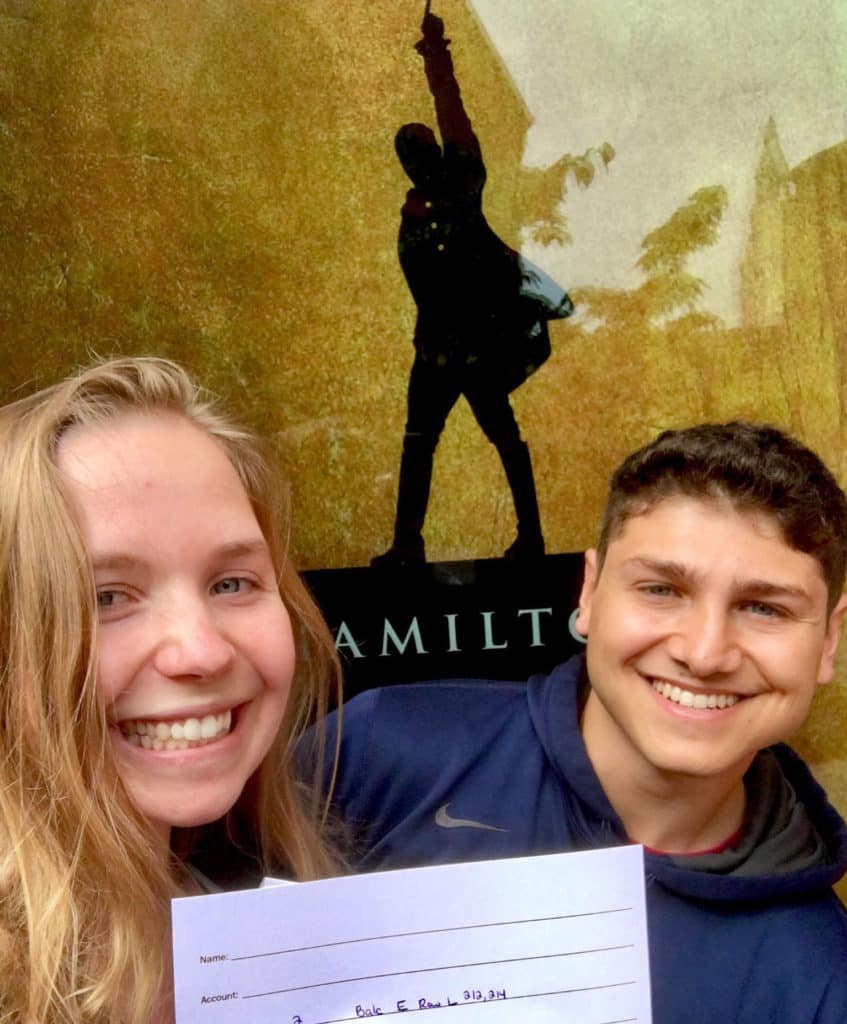

Both professors and students alike are excited for the show to come to Hartford. Celeste Gander ’19, a human rights major and Hamilton fan, waited in line for four hours to get tickets at the Bushnell, where there were already more than 100 people standing outside when she arrived at 6:00 a.m. the day tickets went on sale. “We were actually there so early that we beat the Bushnell staff. By 8:00 a.m. the line had stretched down the block and a couple people at the front of the line started auctioning off their spots for money,” she said. “I’m excited to see the show because it has pretty much been stuck in my head for the past three years.”

Gander noted that one of her takeaways from the story told in the musical is the importance of writing in allowing people to be strong communicators in society. “Hamilton succeeded by being ahead of his time in terms of his writing and education; ‘Writing his way out’ of negative situations and into new opportunities essentially allowed him to achieve the position in politics that he did,” she said.

Glenn W. Falk, professor of the practice in public policy and law, said that he integrated the musical and related materials into his teaching this semester. “In my course, ‘American Legal History,’ both Hamilton the man and Hamilton the musical played a key role,” Falk said. He assigned his students a book called Historians on Hamilton, a collection of essays from scholars about what the contemporary Hamilton phenomenon means for understanding America’s history, and the extent that the musical speaks to historic truths despite being anachronistic.

Students have found that Hamilton offers an interesting way to approach history in a non-traditional way. Jenna Gershman ’20 said that while she was studying the Pulitzer Prize-winning musical in Falk’s class this semester, she realized that Hamilton revitalizes a part of history that had the potential to be forgotten. “Hamilton seemed to change the way that students view American history. The narratives jump off the page and draw the attention of many young students,” Gershman said. “Hamilton approaches the study of history in a dynamic, lively, and invigorating way, ultimately showing that learning history is a way to learn about our society today.”

Associate Professor of History and American Studies Scott Gac incorporates Hamilton into his class in a different way: “My American Studies class, ‘Born in Blood,’ mentions the duel between Hamilton and Vice President Aaron Burr as representative of individual violence, honor, and a male political code.” Gac explained why he thinks the show has popularized the early American era. “There’s an increasing interest in how non-presidential or Congressional figures played central roles in American politics and finance, and Hamilton was among the first to fit that description,” he said.

Hamilton is at The Bushnell Center for the Performing Arts in Hartford from December 11 to 30, 2018. Visit bushnell.org for more information.