New History Created: Students Reflect on Time Spent with the Families of George Floyd and Rodney King

Sitting down with the families of George Floyd and Rodney King, one easily could have focused on the media-driven narratives and videos that rocked the world and reignited the national conversation on police brutality and racism—one nearly two years ago and the other more than 30 years ago. Yet for Trinity students Caleb Prescott ’22 and Renita Washington ’22 and Assistant Professor of American Studies and Human Rights Christina Heatherton, more profound learning came through hearing about the human side of the headlines.

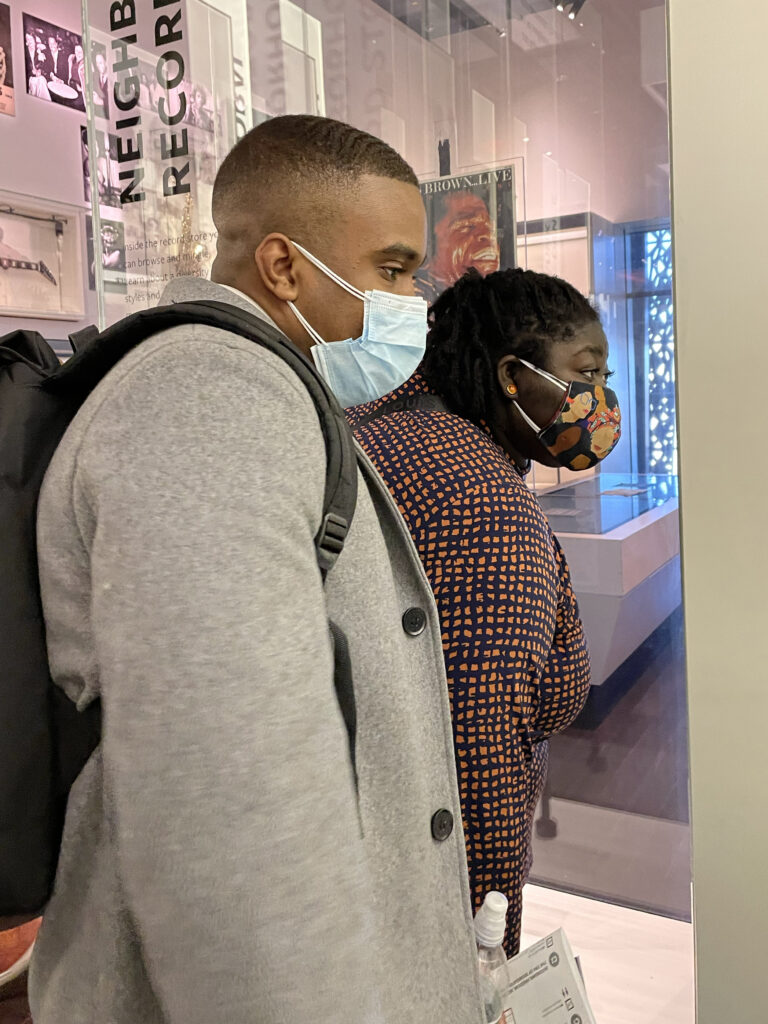

The three joined Trinity President Joanne Berger-Sweeney in Washington, D.C., on February 27 for a historic day coordinated by The Human Gathering, an organization dedicated to facilitating important conversations among influential people. Both families and the Trinity group were invited for a private tour of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture with curator Aaron Bryant and museum director Kevin Young. The Trinity group, the Floyds, and the Kings had not been to the museum or met one another previously.

Simply sharing a day and a family-style meal gave the Trinity students a chance to sit down and talk with both families, human beings to human beings.

“The media had a role in creating their narratives,” said Prescott, who was seated next to Bridgett Floyd, the sister of George Floyd, at a dinner. “I didn’t want to speak for her. This was my opportunity to learn what her narrative is firsthand.”

Prescott, who like many after Floyd’s death were driven to protest for equality, got to meet the families whose lives changed in a matter of moments. This kind of intimacy was unexpected yet served to humanize and contextualize the root of the movement to him. For Washington, the day gave her a sense of “how to move forward from the tragedy that happened to these families, but more so understanding that they’re just people at the end of the day,” she said.

Heatherton, co-director of the Trinity Social Justice Initiative with Assistant Professor of American Studies Jordan Camp (who was unable to attend), noted, “The museum itself was just an extraordinary, extraordinary experience.” She added that given the vast size of the collection, she hopes for more opportunities to bring Trinity students to the museum. “We could spend all four years here,” she said. “I was transformed by the visit and am so grateful to go with Renita and Caleb.”

The museum offered a depth of learning that spanned six centuries of curated stories as told through objects and exhibitions—from African societies in the 1400s and the origins of the colonial slave trades to contemporary African American culture and national politics.

For Washington, an educational studies major, one of the hardest themes that emerged was grappling with how to reconcile the stories of violence with a natural desire to protect the innocence of children.

Washington said she was intensely moved by an exhibit dedicated to Emmett Till and the bronze casket that his mother insisted remain open for others to bear witness to the brutality of his murder. Washington grew up in the same Chicago neighborhood, and briefly on the same street, as 14-year-old Till, who was kidnapped and murdered in Mississippi in 1955. As a young girl, she asked adults around her about his death but found many were not equipped to talk about it. “Now as a college student and an educational studies major, I am realizing that they were just trying to protect my innocence as a child.” Washington said. “We got to view the casket, and it was scary. It was so small.”

For Prescott, an economics major and aspiring judge, the Reconstruction exhibit brought a moment of revelation. “I saw a banknote from the Freedman’s Savings Bank, which was from when Congress passed in 1865 the first national bank for previously enslaved Black people. They had raised $3 million out of the land that they farmed.”

White bankers defrauded account holders of nearly all of their savings, leading to decades of petitioning and protesting a government that returned little to none of the wealth stolen. For Prescott, he linked this historic corruption to attitudes of distrust toward banks and financial institutions that continues to be seen in the Black community today. “I see the hold it still has to some degree on a community of people,” he said. “Even through the Reconstruction period and everything else in the exhibit, I saw how a group of people had the ability to go through pain and struggle and still find beauty, still cultivate a culture that I call my identity. That was one of the biggest things I took away.”

The group was particularly delighted to see a piece of Trinity College in the museum: a poster from J Dilla and the sixth Trinity International Hip Hop Festival prominently encased on the top floor among ephemera from the likes of Ray Charles, Michael Jackson, Alicia Keys, Prince, Beyonce, and other celebrities.

“Temple is my baby! I was so excited,” said Washington, a student leader of Trinity’s Temple of Hip Hop, which organizes the festival. Washington, who exuberantly yelped when she found the rumored poster, said, “I definitely did not use my museum voice!”

Heatherton paraphrased Bridgett Floyd, who gave the students something to think about as the evening closed: “Today wasn’t only about history but a whole new creation of history.”

Read more about this day in the TIME magazine story, The Families of George Floyd and Rodney King Didn’t Ask to Be Part of History—But They Know They Are.

Learn more about the Trinity Social Justice Initiative here.