Skeleton Crew: Professor Helps Preserve Collection for Future Scholars

Dusty, yes, and often not identified. If Daniel Blackburn could find a date, he was lucky.

But Blackburn has since identified each specimen in the treasure trove of skeletons and models that he uncovered at the Albert C. Jacobs Life Sciences Center when he arrived at Trinity as an assistant professor of biology in the late 1980s.

The collection fills his classroom shelves and display cases, overflowing into an adjacent storeroom, and is a tool upon which he relies to teach vertebrae zoology.

Facing both the specter of his own retirement and the likelihood of a building renovation, Blackburn recently met with Trinity College archivists to discuss how to reconstruct history of the collection.

So many of the pieces are irreplaceable, said Blackburn, as he surveyed the group. Many now could not be purchased legally for any price.

“The specimens are fragile,” said Blackburn, the Thomas S. Johnson Distinguished Professor of Biology. “The intrinsic worth of such specimens is widely recognized from a biodiversity standpoint, and now that diversity is being lost with breathtaking rapidity.”

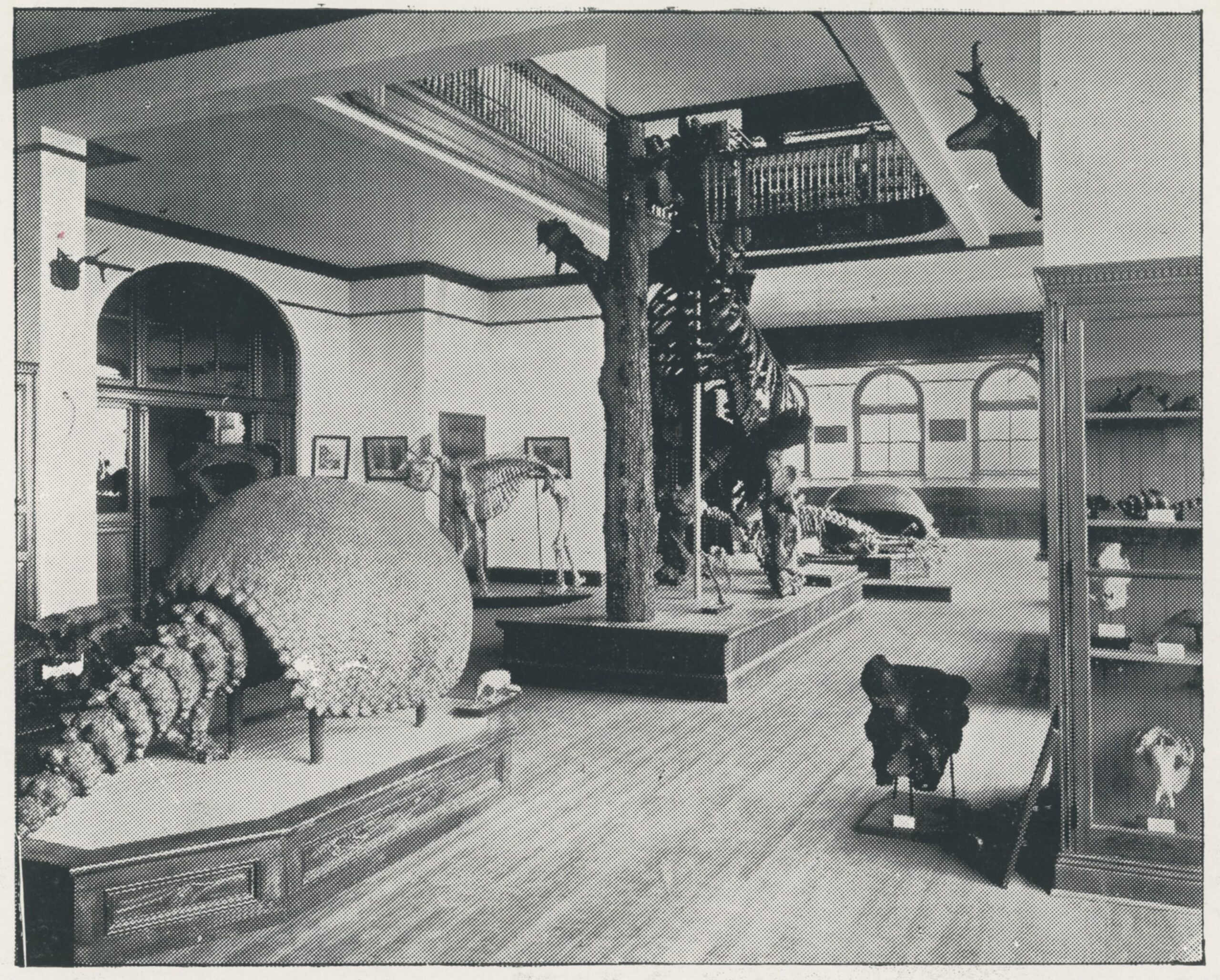

In the early 20th century, few prominent liberal arts colleges could boast of a natural history museum. Both Amherst College and Wesleyan University had such collections, as did Trinity.

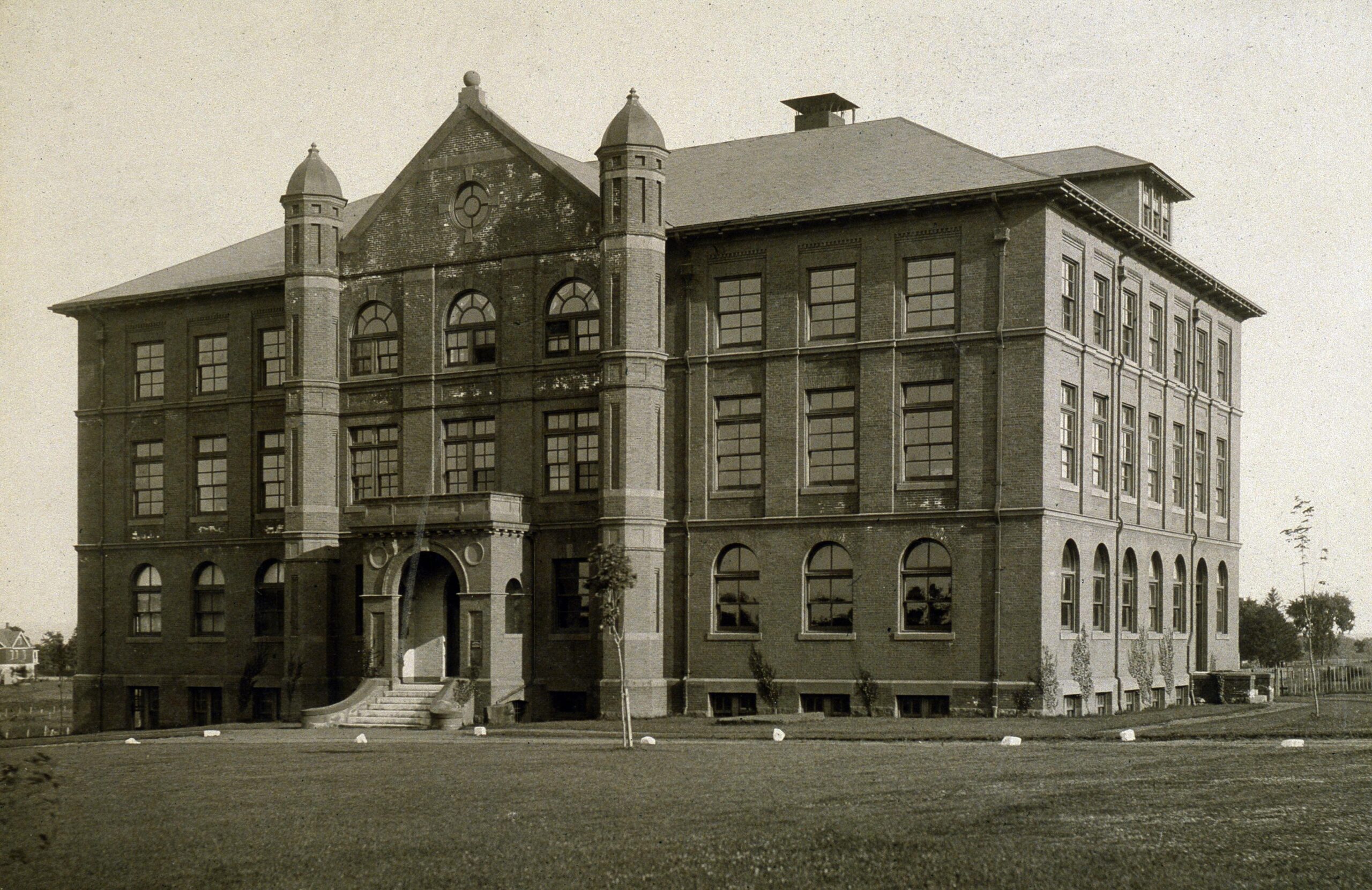

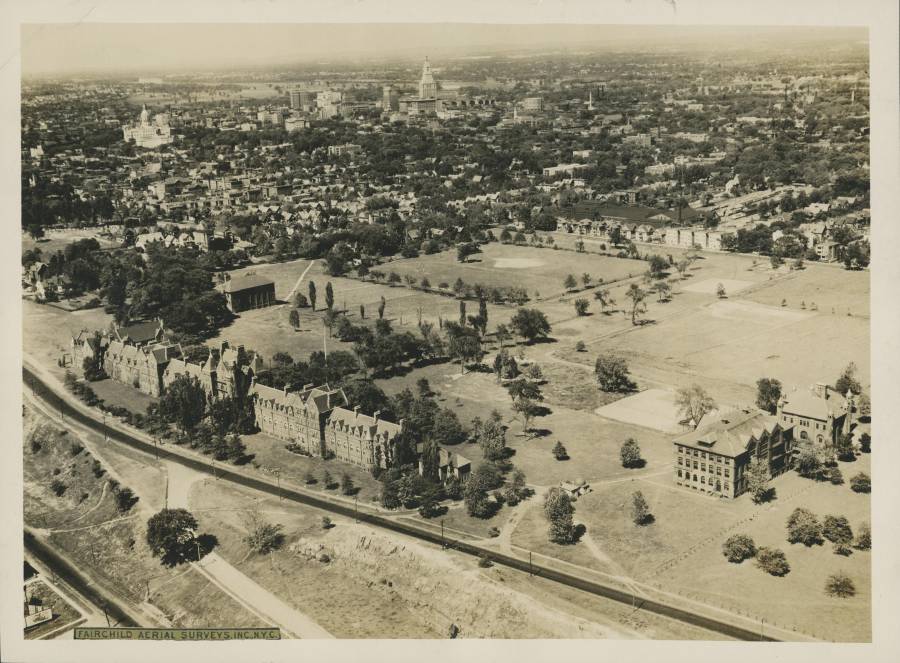

Once photographed in all their splendor at Trinity’s Boardman Hall of Natural History, the world-class collection was used in the early education of students. Boardman stood in the middle of what is now Gates Quad from 1900 until it was demolished in 1971.

The oldest piece in the collection, tagged with the year 1888, predates even that former building, said Blackburn. And the northern fur seal on an upper shelf was nearly extinct in the early 1900s, before it made a comeback.

Moving around the room, Blackburn reeled off the names of the largest skeletons: an Indian elephant, horse, and llama. A Nile crocodile skull is from one of the largest of the land vertebrates. An Amazonian howler monkey, a dugong skull, and a rare echidna from New Guinea are displayed near the more locally common snapping turtle, mole, and salamander.

Moving around the room, Blackburn reeled off the names of the largest skeletons: an Indian elephant, horse, and llama. A Nile crocodile skull is from one of the largest of the land vertebrates. An Amazonian howler monkey, a dugong skull, and a rare echidna from New Guinea are displayed near the more locally common snapping turtle, mole, and salamander.

Each partial or full skeleton reveals a story of evolution, or locomotion, or diet.

“Did you know you can tell the gender of a lion by its skull?” Blackburn asked pointing to the African lion skeleton before pivoting to another display. “I can tell this is a snapping turtle skull because of the size of [space for] the jaw muscle in its head.”

In his courses, Blackburn, a past a winner of the Thomas Church Brownell Prize for Teaching Excellence, situates his students in the path of evolution. Any bone in the human body can be equated to a bone in the body of another mammal, he said. For example, the clavicle in humans exists as a vestigial bone in cats and dogs because evolution determined the quadruped runners would not benefit, he said. “Function and evolution are all captured in the skeleton itself.”

When Boardman Hall was torn down, some of the collection was apparently dispersed. The geology collection was donated to other museums, said Amanda Matava, Trinity’s digital archivist.

Images and an old paper trail led Matava to locate some of the Boardman Hall items at the University of Connecticut and Yale Peabody Museum.

Other pieces in the collection have not been located. Two of the models pictured in popular black-and-white images of the Boardman Hall interior, for example, have not been found: a giant ground sloth and giant armadillo, both from the Pleistocene Era.

Over the years, additional pieces have found their way in.

One day, Blackburn arrived at the Department of Biology to find a wired skeleton of a human hand in his mailbox. Someone reportedly found the piece on Broad Street and turned it over to Trinity. Separately, Blackburn accepted a wallaby skeleton from someone in Western Connecticut. Initially listed on eBay, the Australian wallaby did not fetch any buyers, so the owner agreed to donate it to the College.

Inventorying the skeletons with written records that are accompanied by photos of the items, is critical to maintain the collection for future generations, according to the archivists.

Sarah Raskin, associate dean for faculty development and Charles A. Dana Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience, discussed the plan for the collection during the expected renovation. All items will be carefully inventoried, packed, stored, and then brought back to the newly renovated Jacobs Life Sciences Center, she said.

The collection will continue to be used in courses that cover comparative anatomy and evolution.

“We have to prepare our students for the world they’ll inherit,” said Blackburn, who added, “I’d like to think that when I’m done with my skeleton, I’d love to hang out in a lab like this.”

Maintaining the Past

Maintaining the Past

In 1891, the College announced that a “biological laboratory” or natural history building would be its next project. The Trustees immediately began a fundraiser, estimating it would cost $40,000. Unfortunately, in 1893, the nation succumbed to an economic depression. The fundraiser was revived in subsequent years.

Ground was broken on the building in 1899, and it was formally dedicated a year later under the name “The Hall of Natural History.” The building remained unnamed until 1901, when the Trustees voted to name it in honor of the Hon. William Whiting Boardman, L.L.D., who died in 1871 and served as a trustee for 39 years.

Boardman Hall of Natural History (bottom right) stood behind Cook Hall in the middle of what is now Gates Quad.

When it opened in 1900, the Boardman Hall housed Trinity's Museum of Natural History, and the laboratories and classrooms of the Biology and Natural Sciences departments.

The building was 122 feet long and 72 feet wide with 3 stories in the shape of a parallelogram.

The first floor contained lecture rooms, a library, and work spaces. The second floor consisted of botanical and other laboratories, corresponding libraries, and work spaces, and the third floor contained zoology as well as spaces for post-graduate courses.

The basement provided space for Geology and Mineralogy departments and an aquarium and rooms for cold storage.

By the 1960s, the Life Science and Biology departments had outgrown the outmoded Boardman Hall and the museum had been relegated to the first floor as other departments took over. Bringing Boardman Hall up to code would be exorbitant. The building was razed in 1971.

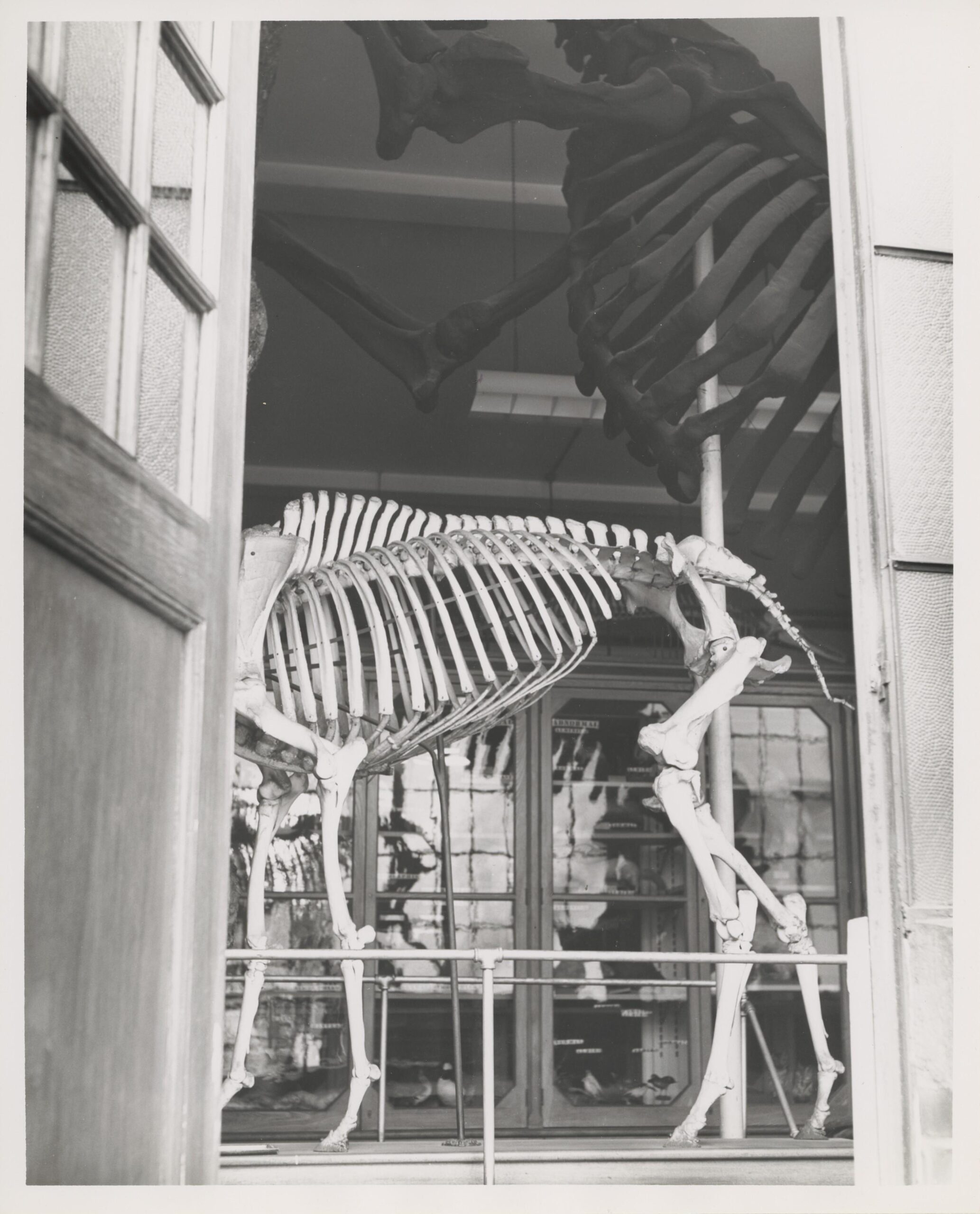

Many of the animal models and skeletons were moved to the Albert C. Jacobs Life Sciences Center, including a porpoise (pictured).

The base of the elephant.

A horse (pictured), llama, and elephant are the largest items in the collection.

Smaller models and skeletons fill display cases.

A dugong skull and an Amazonian howler monkey.

Boardman Hall images supplied by the College Archives. Text taken from Encyclopedia Trinitiana.

In 1891, the College announced that a “biological laboratory” or natural history building would be its next project. The Trustees immediately began a fundraiser, estimating it would cost $40,000. Unfortunately, in 1893, the nation succumbed to an economic depression. The fundraiser was revived in subsequent years.

Ground was broken on the building in 1899, and it was formally dedicated a year later under the name “The Hall of Natural History.” The building remained unnamed until 1901, when the Trustees voted to name it in honor of the Hon. William Whiting Boardman, L.L.D., who died in 1871 and served as a trustee for 39 years.

Boardman Hall of Natural History (bottom right) stood behind Cook Hall in the middle of what is now Gates Quad.

When it opened in 1900, the Boardman Hall housed Trinity's Museum of Natural History, and the laboratories and classrooms of the Biology and Natural Sciences departments.

The building was 122 feet long and 72 feet wide with 3 stories in the shape of a parallelogram.

The first floor contained lecture rooms, a library, and work spaces. The second floor consisted of botanical and other laboratories, corresponding libraries, and work spaces, and the third floor contained zoology as well as spaces for post-graduate courses.

The basement provided space for Geology and Mineralogy departments and an aquarium and rooms for cold storage.

By the 1960s, the Life Science and Biology departments had outgrown the outmoded Boardman Hall and the museum had been relegated to the first floor as other departments took over. Bringing Boardman Hall up to code would be exorbitant. The building was razed in 1971.

Many of the animal models and skeletons were moved to the Albert C. Jacobs Life Sciences Center, including a porpoise (pictured).

The base of the elephant.

A horse (pictured), llama, and elephant are the largest items in the collection.

Smaller models and skeletons fill display cases.

A dugong skull and an Amazonian howler monkey.

Boardman Hall images supplied by the College Archives. Text taken from Encyclopedia Trinitiana.